With Hallowe’en nearly upon us, many parents will be telling their children tales of ghouls and ghosts that can be found in haunted houses. Adults will entertain themselves by watching horror movies and other productions where other-worldly creatures and monsters intrude upon peaceful and civilised spaces to threaten the status quo and the existing order of things. Most of us know that ghosts, spirits, and the like are the stuff of legend and lore and tend not to believe the mythology associated with them. But many people in contemporary society do believe in myths about groups of people that are different to the rest of ‘us’, who exhibit different social norms and values to the mainstream population, and who invoke fear and dread in many of us. Many people watch the behaviour of ‘the underclass’,[1] in the name of entertainment, with a mixture of fear, horror, fascination, and contempt. The ‘underclass’, it is believed, can be found in certain locations. There is a long history to such beliefs.

|

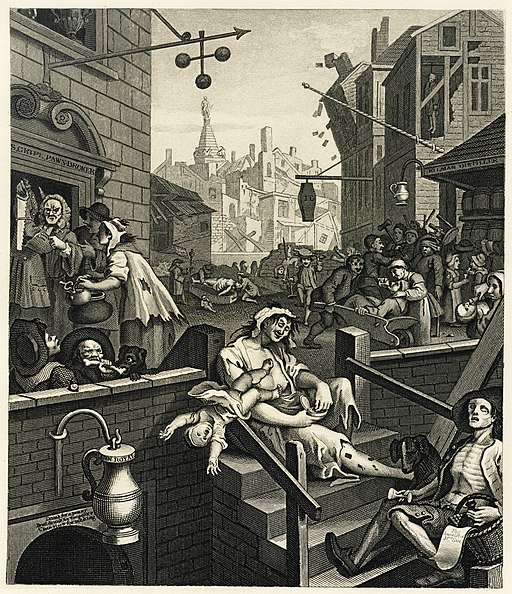

| William Hogarth's depiction of London vice, Gin Lane. |

As interesting as any of those newly-explored lands which engage the attention of the Royal Geographic Society – the wild races who inhabit it will, I trust, gain public sympathy as easily as those savage tribes for whose benefit the Missionary Societies never cease to appeal for funds.William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army argued in 1890 that certain areas of London were like parts of Africa that had just been discovered by explorers such as Henry Morton Stanley Africa, and were similarly full of primitives and savages. In 1977, the sociologist E.V. Walter noted that, whilst such beliefs had changed somewhat, traces of them remained:

In all parts of the world, some urban spaces are identified totally with danger, pain and chaos. The idea of dreadful space is probably as old as settled societies, and anyone familiar with the records of human fantasy, literary or clinical, will not dispute a suggestion that the recesses of the mind conceal primeval feelings that respond with ease to the message: ‘Beware that place: untold evils lurk behind the walls’. Cursed ground, forbidden forests, haunted houses are still universally recognised symbols, but after secularisation and urbanisation, the public expression of magical thinking limits the experience of menacing space to physical and emotional dangers.[4]

Indeed, in recent times, the former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Ian Duncan Smith argued that the television programme Benefits Street offered the middle classes a window into the ‘twilight world’ of neighbourhoods where many people received financial support from the state.[5] The ‘twilight world’ of welfare dependency that Duncan Smith refers to elicits feelings of mystery, anxiety, and the unfamiliar, feelings of nervous excitement that the original social explorers must have felt in the late nineteenth century or what middle class travellers of today might experience whilst ‘doing the slum’ on foreign holidays.

Indeed, in recent times, the former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Ian Duncan Smith argued that the television programme Benefits Street offered the middle classes a window into the ‘twilight world’ of neighbourhoods where many people received financial support from the state.[5] The ‘twilight world’ of welfare dependency that Duncan Smith refers to elicits feelings of mystery, anxiety, and the unfamiliar, feelings of nervous excitement that the original social explorers must have felt in the late nineteenth century or what middle class travellers of today might experience whilst ‘doing the slum’ on foreign holidays.Whilst the words have changed slightly, the myth of a dangerous ‘underclass’ who dwell in ‘dreadful enclosures’ or ‘sink estates’, and who represent a threat to wider society remains. If we want a real horror story for Hallowe’en, we need look no further than how large sections of society view a mythical ‘underclass’ and how they view the places associated with impoverished communities.

Dr Stephen Crossley is a Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Northumbria University. His first book In Their Place: The Imagined Geographies of Poverty is out now with Pluto Press. He tweets at @akindoftrouble

References:

- John Welshman, Underclass: A History of the Excluded Since 1880 (2nd edition), London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

- Seth Koven, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London, Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2004.

- George Sims, How the poor live, London: Chatto & Windus, 1883, p1.

- E.V. Walter, Dreadful Enclosures: Detoxifying and Urban Myth, European Journal of Sociology, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1977), p 154.

- BBC News online, Benefits Street reaction shows poor 'ghettoised', says Duncan Smith, 23 January 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-25866259 [Accessed 27 November 2016]

Images:

- William Hogarth [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Generations' (8690911868_23ce2c05a0_z) by ‘Byzantine_K’ via Flickr.com, copyright © 2013: https://www.flickr.com/photos/november5/8690911868

No comments:

Post a Comment