Given ongoing budget cuts and diminishing local capacity, one might be forgiven for thinking that soon public health practitioners will only be responding to emergencies, such as disease outbreaks and substance abuse epidemics. Fighting these public health fires would leave little time and resources for prevention and working with other public organisations. An event co-organised by Fuse, Durham County Council and Darlington Fire & Rescue Service recently proved quite the opposite: fire fighters and other public organisations are very capable of ‘doing’ public health.

|

| Can public health researchers learn a trick or two from fire fighters? |

In Durham, the Fire and Rescue Service implemented so-called Health and Wellbeing Visits. As part of home visits to check fire safety, fire fighters ask residents questions about their health and wellbeing (e.g. about falls, smoking and alcohol use, heating and loneliness and isolation) and provide them with advice or signpost residents to relevant services to address any health concerns.

Over the past year (Feb 2016 – Jan 2017), no less than 15,732 Health and Wellbeing Visits have taken place with over 1,800 referrals to various services in Durham and Darlington, accessing vulnerable residents that are often not on public health’s radar. Because of their trusted reputation, the Fire and Rescue Service can get behind the front doors of these people and help them access health services. Perhaps not surprisingly most referrals relate to loneliness and isolation, with an ageing population keen to live at home independently but with a social care system lacking resources to support these people in and outside their homes.

Even the police is getting in on the act of public health prevention with partnerships being established between health and the police across the UK to support, among others, suicide prevention and reduce alcohol-related harm, as was recently illustrated in a Public Health England paper.

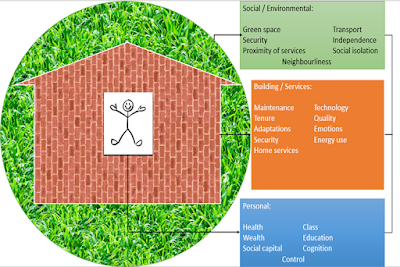

In turn, public health practitioners are taking on new activities that were previously deemed outside of their scope. For instance, the Durham County Council’s public health team is actively supporting energy efficiency improvement schemes (such as Warm and Healthy Homes), in recognition of the link between excess winter death and cold houses. Poor quality housing, low incomes and high energy costs result in residents having to choose between food or fuel. To prevent residents from having to make that choice, council officers are providing tenants at high risk (e.g. people with cardiovascular and respiratory conditions) with new central heating, boiler repairs, home insulation and energy saving advice.

This blurring of boundaries between public professionals is not new, but public health moving back into local authorities has created opportunities for linking prevention activities across a wider range or organisations. The event provided many other examples of this, e.g. GPs prescribing boilers to patients with long-term conditions and Citizens Advice providing welfare rights advice to elderly residents.

This new boundary blurring builds on existing policy initiatives, such as Making Every Contact Count and Health in All Policies, which all involve the wider public health system. Participants at the event made it clear though that this is not a simple cost-saving exercise, allowing councils to pass the public health buck to other parts of the system. Instead, these new partnerships are characterised by a genuine exchange of knowledge and practices between public organisations at the front-line. It highlights a new way of working that recognised joint priorities and the values of other professions to achieve these priorities through the sharing of resources and by taking on new roles. As Professor David Hunter outlined in his presentation at the start of the event, these new partnerships require a different form of leadership, which is less hierarchical and formal, not so much concerned with Key Performance Indicators and commissioner-provider splits, but more focused on the value of relationship building, trust and 'soft' skills.

The event provided a platform for looking at these new partnerships and the evidence for their effectiveness. If anything, it highlighted a challenge for public health academics to research these new partnerships: how to make sense of the contribution of each partner in a system where boundaries are rapidly blurring? Maybe public health researchers can learn a trick or two from fire fighters.

Find out more about the event: Creating Healthy Places in the North East: the Role of Fire and Rescue Services and Fuel Poverty Partnerships

Photo attribution: "Rochdale Fire Station Opening Day" by Manchester Fire via Flickr.com, copyright © 2014: https://www.flickr.com/photos/manchesterfire/13288225965/