You may have thought Coca-Cola invented Christmas. In a sort of way, they did of course. Arguably, modern Santa was designed by an advertising campaign for Coca-Cola in 1933 (Forsyth 2016). And, Santa, whether in the twentieth or twenty-first century, is all about encouraging us to consume. In Coca-Cola’s case, a sweet brown liquid that should logically have absolutely nothing to do with a winter celebration in, originally at least, the Northern Hemisphere.

Coca-Cola has been creative at making up traditions as part of their marketing campaigns since the soft drink was invented in Atlanta, USA, in the late nineteenth century. They have been muscling in on our favourite cultural practices pretty much ever since, in their growth to become a hugely successful and profitable transnational corporation. They have been involved with the Olympics since 1928 when vendors set up branded kiosks in Amsterdam (Keys 2004). A similar relationship with the FIFA World Cup from 1975 was seen as critical at expanding Coca-Cola’s influence into China and the Arab countries (Sugden and Tomlinson 1998).

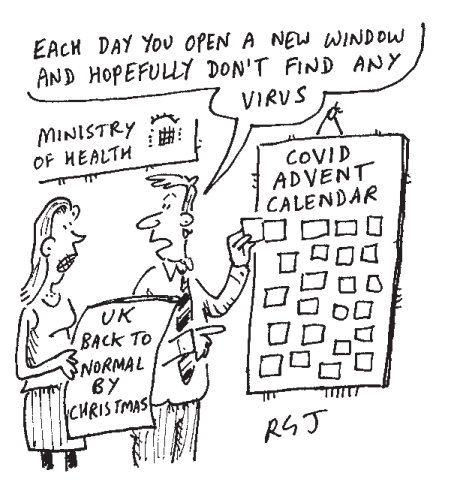

Coca-Cola expert at manipulating our deepest wishes and our emotions whether they are talking Christmas or football. The pandemic may have prevented their Christmas Truck tour in the UK, but, never fear, their international marketing department is on the case. A two and a half minute commercial on YouTube featuring a little girl and her Dad’s attempts to deliver her letter to Santa at the North Pole had already received over 37 million views at the time of writing, whilst pulling at our heart strings.

Professor Dame Sally Davies, the previous Chief Medical Officer in England, wrote, “Commercial companies use a range of strategies and other approaches to promote products and choices that affect human and environmental health, defined as the commercial determinants of health” (Davies 2019 Annex D, p.4). And Coca-Cola are the masters. Luke Allen (Allen 2020) described the corporation as “virtually a cartoon villain in many public health circles” (p.29). Commercial determinants of health can be divided into four channels in which transnational corporations influence health (Kickbusch et al. 2016). Let’s consider how Coca-Cola use these channels.

The marketing is the most obvious. The red and white Coca-Cola brand is ubiquitous. This year the Christmas Truck Tour will not be visiting Liverpool or Glasgow and other major British cities. But the corporation’s partnership with the Premier League enabled it to tour those city centres in 2019.

Coca-Cola expert at manipulating our deepest wishes and our emotions whether they are talking Christmas or football. The pandemic may have prevented their Christmas Truck tour in the UK, but, never fear, their international marketing department is on the case. A two and a half minute commercial on YouTube featuring a little girl and her Dad’s attempts to deliver her letter to Santa at the North Pole had already received over 37 million views at the time of writing, whilst pulling at our heart strings.

Professor Dame Sally Davies, the previous Chief Medical Officer in England, wrote, “Commercial companies use a range of strategies and other approaches to promote products and choices that affect human and environmental health, defined as the commercial determinants of health” (Davies 2019 Annex D, p.4). And Coca-Cola are the masters. Luke Allen (Allen 2020) described the corporation as “virtually a cartoon villain in many public health circles” (p.29). Commercial determinants of health can be divided into four channels in which transnational corporations influence health (Kickbusch et al. 2016). Let’s consider how Coca-Cola use these channels.

The marketing is the most obvious. The red and white Coca-Cola brand is ubiquitous. This year the Christmas Truck Tour will not be visiting Liverpool or Glasgow and other major British cities. But the corporation’s partnership with the Premier League enabled it to tour those city centres in 2019.

|

| This year the Christmas Truck Tour will not be visiting major British cities but the corporation’s partnership with the Premier League enabled it to tour those city centres in 2019 |

How about lobbying then? Marion Nestle (2015) has done a great job in describing how the ‘soda industry’ has learned from the tactics of the tobacco industry in funding dubious research. In funding campaigns and legal challenges to taxes on sugary drinks for example.

As many transnational corporations are criticised for the damage that consumption of their products can cause to human health, so, many try to position themselves as good corporate citizens. Coca-Cola adopt the same tactics and support a number of charities such as FareShare, Street Games, the World Wildlife Fund and Special Olympics GB. It’s sad that in a tough world, it’s often left to corporations to fund good causes rather than government. I thought that had been left in the Victorian age rather than reappearing in the twenty-first century. Coca-Cola also support the Department of Transport’s THINK road safety campaign. In this a volunteer is encouraged to be a Designated Driver to bring intoxicated friends home safely from their Christmas parties. The language of a “responsible drinking culture” is all part of the transnational corporations’ tactics of blaming all of us for believing their marketing and over-consuming their products. That’s right, the soaring levels of overweight and obesity and distressing images of tooth decay amongst youngsters in the UK, are all down to us, the irresponsible parents.

Finally, transnational corporations are experts at developing extensive supply chains to amplify their global ambitions. According to Nestle (2015), Coca-Cola claims to sell its products in two hundred countries with only Cuba and North Korea escaping its clutches. And that’s down to US trade embargoes not to Coca-Cola’s marketing executives.

It’s very hard to argue against Coca-Cola’s Christmas truck tour. Food Active and public health advocates have done so for many years being called the fun police along the way and advocates of the nanny state. We can only speculate the reasons why the tour has been scaled back in the North West in recent years (where Food Active largely operates), but we would take some comfort in the idea that our lobbying played a role in steering the truck off course.

Allen (2020), referenced Coca-Cola’s 2018 annual report, to show the corporation spends approximately US$4 billion per year on advertising. And they wouldn’t be spending that kind of money if the advertising didn’t work. The marketing has persuaded some that Christmas isn’t Christmas without the Coca-Cola Truck Tour. Well, you know the Holidays ARE Coming this year. Because this dreadful pandemic has at least kept some of Coca-Cola’s marketing out of our towns. Let’s just hope that the growing link between obesity and Covid-19 (Alberca et al. 2020) may encourage more to consider how we can limit the advertising of Coca-Cola and other transnational corporations that promote their high in fat, sugar and/or salt products to children. And let’s start to kick Coca-Cola out of Christmas.

References:

Alberca, R.W., Oliveira, L.d.M., Branco, A.C.C.C., Pereira, N.Z. and Sato, M.N. (2020) 'Obesity as a risk factor for COVID-19: an overview', Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1-15, available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1775546.

Allen, L.N. (2020) 'Commercial Determinants of Global Health' in Kickbusch, I., Ganten, D. and Moeti, M., eds., Handbook of Global Health, Geneva: Springer International.

Davies, S.C. (2019) Time to Solve Childhood Obesity, London, available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/837907/cmo-special-report-childhood-obesity-october-2019.pdf [accessed 27 November 2020].

Forsyth, M. (2016) 'Coca-Cola didn’t invent Santa ... the 10 biggest Christmas myths debunked', The Guardian, 21 December 2016, available: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/dec/21/coca-cola-didnt-invent-santa-the-10-biggest-christmas-myths-debunked [accessed 27 November 2020].

Keys, B. (2004) 'Spreading Peace, Democracy , and Coca-Cola®: Sport and American Cultural Expansion in the 1930s', Diplomatic History, 28(2), 165-196.

Kickbusch, I., Allen, L. and Franz, C. (2016) 'The commercial determinants of health', The Lancet, 4, 895-896.

Nestle, M. (2015) Soda Politics. Taking On Big Soda (And Winning). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sugden, J. and Tomlinson, A. (1998) FIFA and the Contest for World Football. Who rules the peoples' game? , Cambridge: Polity Press.

Image 2: Coca-Cola Tour Bus. Liverpool, March 2019. Photo courtesy of E.Boyland.

The views expressed in posts are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Fuse (the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health) or the author's employer or organisation.