We were then given the task of picking some cards to describe ourselves as researchers.

These are the lego cards I chose to describe me during the sessions by Nicole Brown, who works with objects as data in research.

The skydiver because I feel like I just ask to do things and hope for the best, the singer because I like to present and talk about PPI (Patient and Public Involvement) in research.

Black widow because she’s a superhero and fights for people who can’t and Rocket because he’s been made up with tech and I felt like he’s a disabled superhero :)

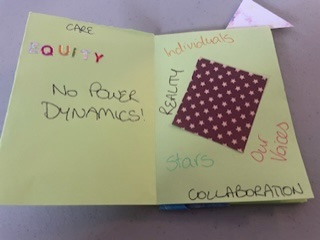

I didn’t know anything about zines and wasn’t aware of the Madzine project to help people with mental health conditions to explain how they feel, get things out and be creative. The session was really interesting giving us some history on zines before we were able to create our own. I made one about a project that I have been working on using some paper with stars on to represent the PPI Group members. A black page for accessibility as we all had different barriers to involvement and some of them were difficult to address, hidden or unknown. Some of the zines that they showed us were amazing: creative, visual, unusual, thought provoking and touching. They plan to create a mobile Madzine library that tours around the country so that people can read the zines and share in the experiences of the creators to increase awareness and understanding of living with mental health conditions.

I didn’t know anything about zines and wasn’t aware of the Madzine project to help people with mental health conditions to explain how they feel, get things out and be creative. The session was really interesting giving us some history on zines before we were able to create our own. I made one about a project that I have been working on using some paper with stars on to represent the PPI Group members. A black page for accessibility as we all had different barriers to involvement and some of them were difficult to address, hidden or unknown. Some of the zines that they showed us were amazing: creative, visual, unusual, thought provoking and touching. They plan to create a mobile Madzine library that tours around the country so that people can read the zines and share in the experiences of the creators to increase awareness and understanding of living with mental health conditions.Kath McGuire (University of Exeter/NIHR School for Public Health Research), led our session talking about working with creative methods, public involvement and research dissemination. I briefly introduced the Fuse podcast and explained the collaborative approach to creating it. People were then able to take a look around the room at the variety of creative outputs that we had brought with us, and a video about how we have creatively communicated research in Fuse (see below). We had a snakes and ladders game to be used with PPI groups, or groups of researchers to evaluate their projects: snakes were barriers and challenges and ladders were successes and wins. We also took posters created by Fuse researchers showing their project results (Emma Adams) and Kath had a Blue Health Rockpool from another project. We took questions and explained how we created the podcast, what its impact had been and answered lots of technical questions about equipment, hosting and distribution. Hopefully accurately!

Attending the conference really broadened my view of research and public involvement. Lots of researchers at the conference felt that by making their work more creative it made it more inclusive. By reducing or removing established barriers to involvement such as language, terminology, education level and academic preconceptions they were able to engage with a wider, more diverse group of people. They could still be academically rigorous and produce research that stands up to peer review and meets publication standards whilst including more people, accessing people with appropriate lived experience of their topic of study and making involvement engaging, interesting and fun!