“He’d found no cure for Crohn’s, or remedy for autism, no vaccine, no nothing in medicine. But now he was a man delivering fear, guilt, and disease to everywhere with an internet connection.”Brian Deer, The Doctor Who Fooled the World

It wasn’t a scientist, not a medical doctor, nor an esteemed health institution, but Brian Deer, an investigative journalist, who researched, compiled, and detailed to the world ‘The fraud behind the MMR scare’. While the adjective to his profession alludes an expectation to the discovery of truth, it’s his journalistic craft that effectively communicates with passion and clarity how the now struck off doc and his associates formulated the non-existent relationship between MMR and autism.

|

| Health promotion takes more than good science, there is an art to the delivery. Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash |

I’m a researcher for the NIHR funded Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science, where we ‘use behavioural science evidence, theory and methods to support decision-making’. Our approach is rigorous and grounded in scientific theory. However, the pandemic has brought into sharp focus that health promotion takes more than good science, there is an art to the delivery. I mean, how else have the sceptics convinced so many that wearing a face covering could be detrimental to health?

Prior to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency approval of the first COVID-19 vaccines, research institutions, health, and Government bodies had been virtually silent on the development process. Some were also critical of how the initial results were released to the world. This reservation to engage with a non-academic audience is partially understandable, we deal in uncertainty and it’s much more than simply crossing the i's and dotting the t's. No researcher worth their h-index wants to put something out into the world that they can’t back-up empirically. The sad fact is though, if we’re not on the front foot keeping the public informed of the vaccine trial process and approval milestones, then there’s a flock of 'quacks' more than happy to work their grift.

To their credit, they work with the religious zeal of a missionary, flooding every corner of the internet knowing our vulnerability to the illusory truth effect. While promotion is focused on social media, their word is also preached in podcasts and proliferated through e-commerce. Take a look at Amazon. Their charitable programme AmazonSmile has reportedly donated thousand of dollars to a vaccine misinformation soil pipe, and high ranking books on “vaccines” include: ‘Anyone who tells you vaccines are safe and effective is lying’, ‘The COVID vaccine: and the silencing of our doctors and scientists’, and ‘Vaccine-nation: poisoning the population, one shot at a time’. There is also the subtly titled: ‘******’s review of critical vaccine studies’, that gives the allusion of a systematic review (though don’t expect it to be listed in the Cochrane Library) but shares a publisher with the essential intergalactic phrasebook ‘Ambassador between worlds’ that provides answers to: What do extraterrestrials think about our religious beliefs, sexual attitudes, and goals in life? But most depressing of all, prominence is given to the book authored by the struck off doc, the man at the centre of Deer’s investigation.

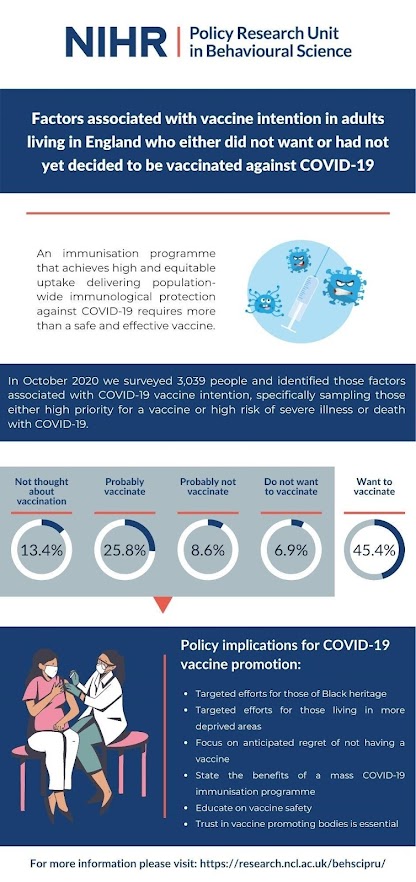

Before the first COVID-19 shots were available, to understand vaccine attitudes my Unit delivered a survey using belief-based statements in adults living in England who did not want, were yet to consider, or were not sure whether to vaccinate against COVID-19. This included their agreement to some of the more 'out-there' theories, including our own fictionalised theory that “Mass coronavirus vaccination is a ploy by environmental lobbyists to sterilise billions of people to reduce population growth”, to which 117 (7%) of respondents agreed to. While my literary intention here is to shock, I suspect that the pandemic has made you immune to such statistics. The problem is that once such views have taken root the typical counter arguments using facts are insufficient, and potentially detrimental in combating misinformation.

The vaccine rollout has been the biggest, most ambitious immunisation programme ever in the UK. It’s a historic achievement by the NHS, ably supported by the Vaccine Taskforce. But as we now reflect, it’s my view that if the Government, healthcare providers and research institutions had provided a cohesive, timely, and responsive informative service that detailed and provided a status update on vaccine development, this would have gone a long way to allay many people's rightful concerns. Sadly this reticence to comment continues as speculation increases over approval of jabs for younger children.

The public has shown an enthusiasm to learn a wealth of terminology during the course of the pandemic. My Unit’s work on the comprehension of antibody testing has shown that this isn’t easy, but it’s something that we shouldn’t shy away from. Patient and public involvement in research is vital to ensure that our lay outputs are fit for purpose and we should all consider how we can be better at science translation. Speaking on camera or on live radio is incredibly nerve-racking and not for all, but as I recently discovered following a two-hour training course, you don’t need a degree in design to produce a half decent infographic.

While I am advocating for your individual action, we also need to consider what systems, for example the new UK Health Security Agency, could put in place to fulfil the role that was missing during the pandemic. Most pressingly on our horizon is the delayed childhood vaccine strategy. The struck-off doc will be feeling emboldened. He understands and has mastered the artistic skill of communication, delivering his message with the gentle assured cadence of a BBC continuity announcer. In the absence of substantiated evidence, he expertly sows doubt and fear to the masses, and as the infodemic has shown, he is not alone. This is a huge challenge for us in public health research and the online vitriol is scary. But building the evidence-base isn’t enough, we all need to work on at least one aspect of the artistic craft of research promotion. Because if it’s not you, you can be assured that someone else most certainly is.

The views and opinions expressed by the author are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, Newcastle University or Fuse, the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health.

The Policy Research Unit is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) [Policy Research Programme (Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science PR-PRU1217-20501)]. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Images:

1) Lourenço Veado, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons