We would like to wish all of our readers and contributors a very happy festive season. We will return in the New Year - why not make a resolution to blog in 2018 and send us your posts?

Friday, 22 December 2017

Friday, 15 December 2017

Not addicted but still having an impact: children living with parents who misuse drugs and alcohol

Guest post by Dr Ruth McGovern, Institute of Health & Society, Newcastle University

There is growing political interest in the misuse of alcohol and drugs by parents and its impact upon children. The newly published Drug Strategy 2017 highlights drug and alcohol dependent parents as a priority group with an estimated 360,000 children living with parents who are dependent upon alcohol or heroin.

As a registered social worker, I have often identified ‘dependent parental substance misuse’ as a risk factor in many ‘child in need’ assessments conducted by Children’s Services. Around half of all child protection cases, recurring care proceedings (repeat children removed and placed into local authority care) and serious case reviews (enquiries following child death or serious injury where neglect or abuse is known or suspected) involve parents who misuse substances. However, the impact of parental substance misuse is not limited to addicts. The number of children living with parents who misuse but aren’t dependent upon alcohol and drugs is likely to be substantially more than the number of children living with those who are addicts. As such, greater harm in the population as a whole is likely to be experienced by these children.

There is growing political interest in the misuse of alcohol and drugs by parents and its impact upon children. The newly published Drug Strategy 2017 highlights drug and alcohol dependent parents as a priority group with an estimated 360,000 children living with parents who are dependent upon alcohol or heroin.

As a registered social worker, I have often identified ‘dependent parental substance misuse’ as a risk factor in many ‘child in need’ assessments conducted by Children’s Services. Around half of all child protection cases, recurring care proceedings (repeat children removed and placed into local authority care) and serious case reviews (enquiries following child death or serious injury where neglect or abuse is known or suspected) involve parents who misuse substances. However, the impact of parental substance misuse is not limited to addicts. The number of children living with parents who misuse but aren’t dependent upon alcohol and drugs is likely to be substantially more than the number of children living with those who are addicts. As such, greater harm in the population as a whole is likely to be experienced by these children.

I have been part of a group of academics and clinicians who have recently concluded a rapid evidence review funded by Public Health England (PHE). The review found evidence that parents who misuse, but aren’t dependent on substances, can have a significant impact on the physical, psychological and social health of their child. For instance, in early childhood we found that children of mothers misusing alcohol [1] were twice as likely to suffer a long bone fracture and five times as likely to be accidentally poisoned, than children whose mothers do not drink heavily. Children of mothers misusing alcohol or drugs are also more likely to require outpatient care or to be hospitalised due to injury or illness, and for longer. The impact of substance misuse by parents continues into adolescence, with our review showing an increased likelihood of antisocial, defiant and violent behaviour in late adolescence as well as substance misuse by the child. However, many of these children and families are not identified as being affected by the substance misuse of a parent and subsequently do not receive the help they need in the form of an intervention.

Therefore, our review also examined the evidence for effective interventions to help reduce the numbers of parents misusing alcohol and drugs. Family-level interventions, particularly those that offer intensive case management, or those which provide parents with a clear motivation (such as those linked to care proceedings) show promise in reducing the problem. Unfortunately, there was little research examining the effectiveness of interventions for parents misusing but not dependent on alcohol and drugs.

|

| PAReNTS study logo |

References:

- Below the age of 10 years, much of the evidence focuses on mothers with alcohol misuse problems as most caregiving is carried out by mothers during early years.

- The AUDIT-C is a 3-item alcohol screen that can help identify persons who are hazardous drinkers or have active alcohol use disorders (including alcohol abuse or dependence): https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/tool_auditc.pdf.

- This programme was highlighted by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence alcohol prevention guidance (PH24): https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph24.

Image credits:

- First image: Copyright: Alcohol Concern April 2008. Taken from the report 'Keeping it in the Family Growing up with parents who misuse alcohol'. ISBN number 1 869814 92 4: https://www.alcoholconcern.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=399c1dd7-1cb3-407d-a093-b3d486ac034d

Friday, 8 December 2017

Is it possible to have a research career without being a workaholic?

Posted by Peter van der Graaf, AskFuse Research Manager, Teesside University

This was one of the burning questions that NIHR trainees put to an esteemed panel of career advisers at their annual meeting in Leeds. Every year the National Institute for Health Research brings together their trainees at a two-day event to network, share experiences, take part in workshops and generally learn more about the largest national clinical research funder in Europe. This year’s theme: Future Training for Future Health.

This was one of the burning questions that NIHR trainees put to an esteemed panel of career advisers at their annual meeting in Leeds. Every year the National Institute for Health Research brings together their trainees at a two-day event to network, share experiences, take part in workshops and generally learn more about the largest national clinical research funder in Europe. This year’s theme: Future Training for Future Health.

With all these bright minds in the room and a dedicated session on successful fellowships and grant applications, you would think ‘top tips on surviving an interview’ and ‘what mistakes to avoid in an application’ would be on the top of their list. However, after several inspiring presentations from previous and current award holders who had climbed the academic ladder - including Fuse Director Ashley Adamson a NIHR Research Professor - participants were equally, if not more, concerned about maintaining a healthy life-work balance.

While Brexit questions made a brave entrance (Q: How will Brexit affect future research? A: In the long term, not all all!), they could not knock questions about mental health and wellbeing from the top spot. When Ashley included pictures of her son in a musical-inspired animation of her academic pathway (follow the yellow-brick road!) to explain that she preferred part-time work to spend more time with her family, participants immediately asked “but how do you fit family in with an academic career?”.

New gadget SLI.DO was introduced by the NIHR at the meeting this year: participants could submit questions through a mobile app, which others could vote to be answered by the panel (Bush Tucker Trial for academics). Not having to stand up in front of an audience to say who you are, might have given some participants the confidence to ask uncomfortable questions. The honest and open stories from the presenters about their own struggles and failures in academia (“my new post oscillated between agony and despair”) might also have contributed to this confidence.

Experiences of stress and concerns over mental health in academic careers were acknowledged throughout the conference in various presentations and workshops. This was perhaps most evident in the closing session by Paul McGee (aka The Sumo Guy) who emphasises the importance of looking after your mental health in academia. His four key messages (be kind to yourself; get perspective; hippo time - to wallow - is ok; and keep pushing) resonated with many participants and provoked a strong response on social media.

As public health researchers, we are familiar with these messages. In our studies, we underline the link between physical and mental health, express our deep concern over the lack of mental health services and highlight the importance of resilience training from an early age in schools. However, it appears that we are not very good at applying this evidence to our own life and work.

This was recently confirmed by a systematic review of published work on researchers' well-being featured in the Times Higher Education. The review, commissioned by the Royal Society and the Wellcome Trust, found that academics face higher mental health risk than many other professions. Lack of job security, limited support from management and weight of work-related demands on time were listed as factors affecting the mental health of those who work in higher education.

Given this evidence, is it possible to have an academic career and stay healthy? Despite the questions raised at the annual event, the NIHR trainees were keen to acknowledge positive mental health messages: you can have a life and family outside academia (no need to be workaholic, although being a data geek is acceptable*); it’s ok to be different and carve your own path to develop your intellectual independence; and most of all: the key to success is self-care and not funding.

* An after-dinner presentation by @StatsJen taught us that there is a perfect correlation between eating cheese and death by entanglement in bedsheets. Will midnight cheese feasts be the next public health scare?

|

| Follow the yellow brick road to academic success |

New gadget SLI.DO was introduced by the NIHR at the meeting this year: participants could submit questions through a mobile app, which others could vote to be answered by the panel (Bush Tucker Trial for academics). Not having to stand up in front of an audience to say who you are, might have given some participants the confidence to ask uncomfortable questions. The honest and open stories from the presenters about their own struggles and failures in academia (“my new post oscillated between agony and despair”) might also have contributed to this confidence.

|

| Paul McGee emphasises the importance of looking after your mental health in academia |

As public health researchers, we are familiar with these messages. In our studies, we underline the link between physical and mental health, express our deep concern over the lack of mental health services and highlight the importance of resilience training from an early age in schools. However, it appears that we are not very good at applying this evidence to our own life and work.

This was recently confirmed by a systematic review of published work on researchers' well-being featured in the Times Higher Education. The review, commissioned by the Royal Society and the Wellcome Trust, found that academics face higher mental health risk than many other professions. Lack of job security, limited support from management and weight of work-related demands on time were listed as factors affecting the mental health of those who work in higher education.

Given this evidence, is it possible to have an academic career and stay healthy? Despite the questions raised at the annual event, the NIHR trainees were keen to acknowledge positive mental health messages: you can have a life and family outside academia (no need to be workaholic, although being a data geek is acceptable*); it’s ok to be different and carve your own path to develop your intellectual independence; and most of all: the key to success is self-care and not funding.

* An after-dinner presentation by @StatsJen taught us that there is a perfect correlation between eating cheese and death by entanglement in bedsheets. Will midnight cheese feasts be the next public health scare?

Labels:

2017,

AAdamson,

academics,

Brexit,

career,

event,

fellowship,

funding,

grants,

mentalhealth,

networking,

NIHR trainees,

presentations,

PvanderGraaf,

research,

training,

wellbeing,

work:life balance,

workshop

Friday, 1 December 2017

When the Coca-Cola truck comes to your town

Guest post by Robin Ireland, Director of Research at Food Active and Beth Bradshaw, Project Officer at Food Active.

When Coca-Cola announced their 'Holidays Are Coming' truck tour (ironically coinciding with Sugar Awareness Week), our local media in the North West covered the story like it was the first sign of Christmas, the first cuckoo to be spotted in spring.

And in the run up to the big red shiny sugar-laden truck’s arrival to our towns and cities, from Bolton to Liverpool, Manchester to St Helens, the local newspapers will cover the story in page after page of advertorials, telling you where to get your picture taken posing with Coca-Cola's sugary products and even live blogs in some cases.

Following excellent work by Public Health England, by national organisations including Action on Sugar, the Children's Food Campaign and many others, and of course by Food Active in the North West, we know that we must target sugary drinks as part of a strategy to address the tsunami of obesity, type 2 diabetes and dental disease we face in our poorest and most deprived communities. Moreover, as highlighted in a blog by Dr. Alison Tedstone, Director of Diet and Obesity at Public Health England, the truck will be visiting some of our poorest areas which are often disproportionately burdened with higher levels of obesity [2]. As such, a symbol of ill health should not be welcomed nor celebrated within our communities during a season of good will and cheer.

However, this is not only about high sugar drinks. Protecting children from junk food marketing has been outlined as the number one priority in tackling obesity by the Obesity Health Alliance (a coalition of over 40 organisations committed to reducing obesity – of whom Food Active is a member). We must not mistake the Coca-Cola truck for anything but a very high profile marketing stunt. We do not allow products high in fat, sugar and salt to be advertised to children on children’s TV programmes, so why is the Coca-Cola truck welcomed into our communities year on year with such open arms? Speaking at the Socialist Health Alliance Public Health Conference, we called for junk food marketing controls to be extended to cover family attractions such as the Coca-Cola truck, as well as sports sponsorship and marketing communications in schools. By allowing the truck into our towns and cities, we are allowing Coca-Cola to exploit the festive period to market their products to the community – and to children in particular.

Photo © Oast House Archive (cc-by-sa/2.0)

All views expressed in a post are exclusively those of the author or authors.

And in the run up to the big red shiny sugar-laden truck’s arrival to our towns and cities, from Bolton to Liverpool, Manchester to St Helens, the local newspapers will cover the story in page after page of advertorials, telling you where to get your picture taken posing with Coca-Cola's sugary products and even live blogs in some cases.

In previous years, at no time did the reporters consider that not everyone welcomed the truck in their neighbourhood. Many people are concerned that the truck was marketing Coke to children despite the company's protestations that they do not promote their products to the under twelves. Furthermore, in some locations in the North West the truck was allowed to promote their unhealthy drinks to children and families on Council owned landed.

To demonstrate our concern, last year Food Active drafted a letter objecting to Coca-Cola's tour coming to the North West which was sent to the national and regional media. No less than 108 people signed in support including the current and past Presidents of the Faculty of Public Health, five Directors of Public Health, Professors, Doctors, educationalists and of course parents. If we are honest, we were shocked that the letter was almost entirely ignored. It would appear that Coca-Cola's commercial clout and public relations campaign counted more than the collective voice of those who are having to address the results of diets regularly fuelled by liquid sugar.

Just before Christmas 2016, Professor John Ashton and I (Robin) were in contact with the British Medical Journal concerning these issues and were invited to submit an editorial which was published in January [1]. In contrast to their previous experience the media attention was huge including coverage in over 60 regional and national newspapers and interviews on various channels including Sky News and Wales Today.

This year, the media attention and discussions around the Coca Cola Christmas Tour has continued. Before the tour was even announced, a news story hit the local press in the North West from Liverpool councillor Richard Kemp CBE (also Deputy Chair of the Community Wellbeing Board at the Local Government Association of England and Wales), who raised concerns about its arrival in Liverpool given the city is ‘in the grip of an obesity epidemic’ – although we know this is not an issue only in Liverpool – the whole country is in the grip on an obesity epidemic. Once the tour was announced, including six visits to the North West, we were pleased to see none were on council-owned land (in 2016 the truck visited Williamson Square in Liverpool which is owned by the Council)

Following this came a cascade of news stories from local and national newspapers and radio stations. This year, Food Active joined up with Sugar Smart to encourage Directors of Public Health, Council Leads and Clinical Commissioning Group Chairs across the country to sign an open letter to Coca-Cola opposing its arrival, given the health harms associated with the consumption of their products and calling for more responsible marketing during the festive period. The North West represented one quarter of the 29 areas, cities and towns who signed the letter. This advocacy may have helped to prompt a response from Public Health England and Public Health Wales – there is a sense that the argument against the Coca-Cola truck are now being taken seriously and media coverage of the 2017 Coca Cola Christmas Tour is not just about when and where you can get your photo taken - but also the health concerns.

|

| Coca-Cola says that it does not promote its products to the under twelves |

Following excellent work by Public Health England, by national organisations including Action on Sugar, the Children's Food Campaign and many others, and of course by Food Active in the North West, we know that we must target sugary drinks as part of a strategy to address the tsunami of obesity, type 2 diabetes and dental disease we face in our poorest and most deprived communities. Moreover, as highlighted in a blog by Dr. Alison Tedstone, Director of Diet and Obesity at Public Health England, the truck will be visiting some of our poorest areas which are often disproportionately burdened with higher levels of obesity [2]. As such, a symbol of ill health should not be welcomed nor celebrated within our communities during a season of good will and cheer.

Our experience shows us that public health has to be persistent in ensuring our messages are heard in the current victim-blaming culture. There is little point in local authorities spending their ever restricted funds on promoting healthier eating and drinking if each Christmas we allow Coca-Cola and others to highjack our messages. There is certainly no excuse for local authorities at to allow this truck on their land and it is the responsibility of public health advocates to continue to make the case to Give Up Loving Pop in 2018.

References:

- Ireland, Robin, and John R. Ashton. "Happy corporate holidays from Coca-Cola." (2017): i6833. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/content/356/bmj.i6833

- Tedstone, Alison. “An update on sugar reduction”. (2017). Available at: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2017/11/14/sugar-reduction-an-update/

Photo © Oast House Archive (cc-by-sa/2.0)

All views expressed in a post are exclusively those of the author or authors.

Labels:

2017,

BBradshaw,

BMJ,

childhood obesity,

children,

Christmas,

Coca-Cola,

diet,

Faculty of Public Health,

FoodActive,

junk food,

local authorities,

marketing,

media,

PHE,

RIreland,

soft drinks,

sport,

sugar

Saturday, 18 November 2017

‘Afore ye go’… across the border for a cheap pint

John Mooney, University of Sunderland and Sunderland City Council, asks how Scotland’s minimum unit pricing policy would go down in North East England.

John Mooney, University of Sunderland and Sunderland City Council, asks how Scotland’s minimum unit pricing policy would go down in North East England.

Like many former native Scots now living and working in North East England, the geographical, social and cultural parallels are just three areas of overlap that help keep homesickness for my country of origin at bay!

As a public health researcher some less fortunate similarities are often at the forefront of my mind, including a fondness for deep-fried food, an aversion to fresh vegetables and a damagingly long-ingrained culture of heavy drinking. This is accompanied by an almost Scottish-scale public health burden to match. It will come as no surprise that as a whole, the North East has among the worst health statistics for alcohol related harm in England [1].

Of course it is also no coincidence that both North East England and much of Scotland’s central belt, particularly Greater Glasgow and Clyde Valley, have some of the most longstanding and concentrated areas of social deprivation and economic disadvantage in the UK. As recent research from Glasgow University has highlighted [2], deprivation and alcohol related health damage, present a particular kind of “double whammy”, even after adjusting for alcohol intake and other lifestyle factors such as smoking.

With these similarities in mind, there is an inescapable logic in looking to Scotland for a steer in terms of policy interventions that might reduce the unacceptably high public health burden due to alcohol in this part of the World. I refer of course to the introduction of a minimum unit price (MUP) of 50p for a unit of alcohol, which on the basis of rigorously evaluated international studies combined with sophisticated cost effectiveness modelling from the Alcohol Research Group at the University of Sheffield [3], is one of the best evidenced policies for reducing alcohol harm in the population.

Scotland is also at the forefront of (what may eventually lead to) a much more ‘fit-for-purpose’ legislative framework around alcohol licensing and availability: namely the inclusion of 'health' as a licensing objective (or ‘HALO’). In principle, this has the potential to transform the capacity of public health teams in English local authorities to make much more use of information on health harms as part of the licensing process. This would ensure that challenges to new licence applications - however potentially damaging the new licence may be - no longer need to be based exclusively on crime and public disorder evidence. To explore whether HALOs could also be used in England, our team at the University of Sunderland looked at the practicalities and logistics of using health information in English licensing decisions. The results have recently been published by Public Health England [4].

So what are the prospects for importing MUP and health objective policies to North East England?

Thankfully, on both policy and research fronts, there are also significant grounds for encouragement in the North East! Indeed, some of the most progressive public health policies around alcohol harm reduction, such as cumulative impact zones and late night levies, are now well established in a number of local authority areas. This has been possible thanks to strong political will and high profile regional level advocacy for alcohol harm reduction policies from Balance North East [5], which is funded collectively across most North East local authorities. Balance NE has already been calling for better controls on cheap alcohol availability in the wake of the Scottish Policy decision [6].

There is also no shortage of public health alcohol research effort in the North East, with a long tradition of internationally renowned research from the Universities of Newcastle, Teesside and most recently our own contributions to several national level evaluations (such as HALO mentioned above).

In brief, there are many regional policy drivers already in place for North East England to emulate Scotland’s very progressive approach to the reduction of alcohol harms. With regard to the often raised criticism that price based measures such as MUP are ‘regressive’ due to a disproportionate financial impact on the poorest, it is difficult to rival the response of Scottish novelist Val McDermid on Thursday's (16 Nov) BBC Question time: “it’s actually about preventing people in our poorest communities drinking themselves to death with cheap alcohol”. It is difficult to figure out what particular definition of the term ‘regressive’ that this conforms to…

References:

- Local Alcohol Profiles for England [May 2017]: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/local-alcohol-profiles/data#page/0

- Katikireddi SV, Whitley E, Lewsey J, et al. Socioeconomic status as an effect modifier of alcohol consumption and harm: analysis of linked cohort data. The Lancet Public Health 2017;2(6):e267-e76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30078-6

- Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/ph/research/alpol/research/sapm

- Findings from the pilot of the analytical support package for alcohol licensing: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/620478/Alcohol_support_package.pdf

- Balance North East: http://www.balancenortheast.co.uk/about-us/

- Balance North East news item: http://www.balancenortheast.co.uk/latest-news/balance-calls-on-government-to-follow-scotland-on-mup

Images:

- 'cheap booze, hackney' (3892082333_943f3cc70e_o) by ‘quite peculiar' via Flickr.com, copyright © 2009: https://www.flickr.com/photos/quitepeculiar/3892082333 (cropped)

- Courtesy of Alcohol Focus Scotland: https://twitter.com/AlcoholFocus/status/922822671599054848

Monday, 13 November 2017

Public health, social justice, and the role of embedded research

Posted by Mandy Cheetham, Fuse Post doctoral Research Associate and embedded researcher with Gateshead Council Public Health Team

On this date (13 November) in 1967, Martin Luther King was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Civil Law from the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. The speech he gave at the award ceremony is both powerful and moving. It was the last public speech he made outside the US before his assassination in April 1968. You can read it for yourself here or watch it here.

On Sunday 29 October, I had the privilege of being part of the Freedom City 2017 celebrations held on the Tyne Bridge to mark this significant anniversary, inspire people, and stimulate academic debate about potential solutions. Performances across Newcastle and Gateshead came together to mark different civil rights struggles across the globe, including Selma, Alabama 1965, Amritsar, India 1919, Sharpeville, South Africa 1960, Peterloo, Manchester 1819, and the Jarrow March, Tyneside 1936.

I believe our role as writers and researchers in public health is not just to highlight the effects of these grave injustices, but to be part of the solutions, developed with the communities affected. If we accept that we are all caught up in what Dr King described as “an inescapable network of mutuality”, then universities have an important part to play in changing attitudes, working with others, facilitating connections, and inspiring efforts to “speed up the day when all over the world justice will roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream”. (Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Speech on Receipt of the Honorary Degree, November 13, 1967).

I believe our role as writers and researchers in public health is not just to highlight the effects of these grave injustices, but to be part of the solutions, developed with the communities affected. If we accept that we are all caught up in what Dr King described as “an inescapable network of mutuality”, then universities have an important part to play in changing attitudes, working with others, facilitating connections, and inspiring efforts to “speed up the day when all over the world justice will roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream”. (Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Speech on Receipt of the Honorary Degree, November 13, 1967).

On this date (13 November) in 1967, Martin Luther King was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Civil Law from the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. The speech he gave at the award ceremony is both powerful and moving. It was the last public speech he made outside the US before his assassination in April 1968. You can read it for yourself here or watch it here.

Newcastle was the only UK University to award an honorary degree to Dr King in his lifetime. In accepting the honour, he said “you give me renewed courage and vigour to carry on in the struggle to make peace and justice a reality for all men and women all over the world”. As I listened to the speech, it struck me that the three “urgent and indeed great problems” of racism, poverty and war, which Dr King described in his speech, are just as relevant today as they were then. It made me reflect on our role in universities now and on my role as an embedded researcher in Gateshead Council.

|

| That's me on the left |

The celebrations were timely, as I am just finishing an embedded research project in Gateshead, undertaken less than a mile from where we stood on the Tyne Bridge. It has been an inspiring year. I’ve learnt a lot, but I have also seen the devastating effects of austerity and poverty on North East families and communities. The research findings demonstrate all too clearly the continuing impact of the social injustices which Martin Luther King talked about fifty years ago.

I believe our role as writers and researchers in public health is not just to highlight the effects of these grave injustices, but to be part of the solutions, developed with the communities affected. If we accept that we are all caught up in what Dr King described as “an inescapable network of mutuality”, then universities have an important part to play in changing attitudes, working with others, facilitating connections, and inspiring efforts to “speed up the day when all over the world justice will roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream”. (Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Speech on Receipt of the Honorary Degree, November 13, 1967).

I believe our role as writers and researchers in public health is not just to highlight the effects of these grave injustices, but to be part of the solutions, developed with the communities affected. If we accept that we are all caught up in what Dr King described as “an inescapable network of mutuality”, then universities have an important part to play in changing attitudes, working with others, facilitating connections, and inspiring efforts to “speed up the day when all over the world justice will roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream”. (Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Speech on Receipt of the Honorary Degree, November 13, 1967).

I believe embedded research affords us valuable opportunities, to work alongside local communities with colleagues in public health and voluntary sector organisations, to challenge injustices and push for the kinds of social and political change advocated by Dr King.

Photo credits:

Photo credits:

- Martin Luther King Honorary Degree Ceremony: http://www.ncl.ac.uk/congregations/honorary/martinlutherking/. Courtesy of Newcastle University.

- Photo by Bernadette Hobby of "the judge", representing the establishment, about to receive the Jarrow Marchers petition. The judge was made by Richard Broderick sculptor.

- Freedom on the Tyne, The Pageant: http://freedomcity2017.com/freedom-city-2017/freedom-city-tyne/. Courtesy of Newcastle University.

Wednesday, 8 November 2017

Spice up your research life: match-making in public health

Posted by Peter van der Graaf, AskFuse Research Manager, Teesside University

Three years ago, we had a crazy idea: what if Fuse had its own dating service for academic researchers and health professionals? Instead of innovative research findings gathering dust on lonely bookshelves, we wanted to provide a stage for academics and health professionals to meet and discuss how that evidence could be used in practice. We were keen to facilitate early conversations on how to collaborate on research that is useful, timely, independent, and easily understood.

Instead of health practitioners wandering around University campuses, trying to find the right academic to work with, we envisioned an open door leading to a welcoming friendly-faced guide. Someone who could do the matchmaking and help them to find or create evidence for spicing up their policies or interventions.

After checking our idea with various health practitioners in the region to make sure that it would make their hearts beat faster, we launched AskFuse in June 2013: Fuse’s very own rapid responsive and evaluation service with a dedicated match-maker (research manager) in post – that’s me!

Coming from an applied research background in social sciences, this post was certainly a challenge but also an incredibility exiting opportunity to develop something new with the support of an enthusiastic group of people across Fuse. The job has been a steep learning curve, but also a great way to meet a lot of people working in public health across the region, getting to understand their passions and … what keeps them up at night.

I quickly learned that there were many great public health projects and programmes being developed and delivered locally that deserved more attention and research (e.g. My Sporting Chance, Ways to Wellness, Boilers on Prescription). I was encouraged by a real appetite among academics to support this work but felt the frustrations of health professionals caused by budget cuts and the need to decommission services rather than to develop them. I also noticed the limited research evidence informing some of these decision-making processes and the lack of knowledge among academics about how to influence these processes and mobilise their research evidence effectively.

AskFuse has supported more than 270 enquiries from a wide range of sectors, organisations and on topics ranging from Laughter Ball Yoga to Whole Systems Approaches to obesity. We have helped to develop new interventions and evaluated existing ones, made research evidence accessible and understandable, organised events to explore new topics, and pioneered new methodologies; all in collaboration with our policy and practice partners. We have also made mistakes, misunderstood procurement procedures, were not able to help in time, could not find relevant expertise or did not always follow-up on conversations.

Despite these challenges - or perhaps because of them - we have been able to build a dating service that (I think/hope) is perceived as useful by our policy and practice partners, that has helped us to build relationships (even in times of considerable system upheaval with public health moving to local authorities), and has informed new research agendas for Fuse going forward over the next five years as a member of the national School for Public Health Research.

As the service is expanding and my role is changing (I recently became a NIHR Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellow, which I will talk about in another blog), we are looking for a new AskFuse Research Associate to work with me on strengthening the service and taking it in new directions. If you are interested in mobilising knowledge, fancy a challenge and want to work with a fantastic team, why not be part of it?

Three years ago, we had a crazy idea: what if Fuse had its own dating service for academic researchers and health professionals? Instead of innovative research findings gathering dust on lonely bookshelves, we wanted to provide a stage for academics and health professionals to meet and discuss how that evidence could be used in practice. We were keen to facilitate early conversations on how to collaborate on research that is useful, timely, independent, and easily understood.

Instead of health practitioners wandering around University campuses, trying to find the right academic to work with, we envisioned an open door leading to a welcoming friendly-faced guide. Someone who could do the matchmaking and help them to find or create evidence for spicing up their policies or interventions.

After checking our idea with various health practitioners in the region to make sure that it would make their hearts beat faster, we launched AskFuse in June 2013: Fuse’s very own rapid responsive and evaluation service with a dedicated match-maker (research manager) in post – that’s me!

Coming from an applied research background in social sciences, this post was certainly a challenge but also an incredibility exiting opportunity to develop something new with the support of an enthusiastic group of people across Fuse. The job has been a steep learning curve, but also a great way to meet a lot of people working in public health across the region, getting to understand their passions and … what keeps them up at night.

AskFuse has supported more than 270 enquiries from a wide range of sectors, organisations and on topics ranging from Laughter Ball Yoga to Whole Systems Approaches to obesity. We have helped to develop new interventions and evaluated existing ones, made research evidence accessible and understandable, organised events to explore new topics, and pioneered new methodologies; all in collaboration with our policy and practice partners. We have also made mistakes, misunderstood procurement procedures, were not able to help in time, could not find relevant expertise or did not always follow-up on conversations.

Despite these challenges - or perhaps because of them - we have been able to build a dating service that (I think/hope) is perceived as useful by our policy and practice partners, that has helped us to build relationships (even in times of considerable system upheaval with public health moving to local authorities), and has informed new research agendas for Fuse going forward over the next five years as a member of the national School for Public Health Research.

As the service is expanding and my role is changing (I recently became a NIHR Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellow, which I will talk about in another blog), we are looking for a new AskFuse Research Associate to work with me on strengthening the service and taking it in new directions. If you are interested in mobilising knowledge, fancy a challenge and want to work with a fantastic team, why not be part of it?

Labels:

2017,

academics,

askfuse,

collaboration,

dating,

evaluation,

evidence,

job,

knowledge mobilisation,

NIHR SPHR,

partners,

policy,

practice,

public health,

PvanderGraaf,

research,

TeessideUniversity,

translation

Friday, 3 November 2017

Why are veterans reluctant to access help for alcohol problems?

Guest post by Gill McGill, Senior Research Assistant, Northumbria University

Service commissioners/managers and military veterans highlighted a need for greater understanding of ‘veterans’ culture’ and the specific issues veterans face among ‘front line’ staff dealing with substance and alcohol misuse.

National Conference – Northumbria University and Royal British Legion

Veterans Substance Misuse: Breaking Down Barriers to Integration of Health and Social Care

Newcastle United Football Club (Heroes Suite)

Thursday 16 November

More information on the Fuse website.

With Alcohol Awareness Week fast approaching, the Northern Hub for Military Veterans and Families Research is busy planning a national conference to share findings from a project on improving veterans’ access to help for alcohol problems. The project was funded by the Royal British Legion and arose from two questions frequently posed by clinical practitioners working within the field of alcohol misuse services:

- Why is it so difficult to engage ex-service personnel in treatment programmes?

- Once they engage, why is it so difficult to maintain that engagement?

The findings will be discussed in detail at the conference, so please join us there to hear more, but that quick plug aside, we thought we’d give you a sneak preview here!

Paradoxically, although alcohol misuse amongst UK veterans is estimated to be higher than levels found within the general population, we found a limited amount of research that specifically considered alcohol problems among UK veterans. Given that there are an estimated 2.56 million UK military veterans[1], this represents an important, but as yet, largely unaddressed public health issue.

Commissioners and managers of alcohol services expressed the view that veterans have difficulty navigating available support due to ‘institutionalisation’. Yet, when speaking to military veterans themselves, we found no support for this. Such a view point is also potentially problematic in stereotyping veterans as (at least in part) the architects of their own difficulties.

In all cases, it could be said that meaningful engagement with alcohol misuse services was being ‘delayed’ to a significant extent by the veterans involved in our study. They ‘normalised’ their relationship with excessive alcohol consumption both during and after military service and this hindered their ability to recognise alcohol misuse. Yet this was not mentioned by healthcare staff participating in the study. Participants also suggested that seeking help was contrary to ‘military culture’ and that this frame of mind tended to remain with UK military veterans after transition to civilian life. Delay in seeking help often meant that by the point at which help was sought, the problems were of such complexity and proportion that they were difficult to address.

Service commissioners/managers and military veterans highlighted a need for greater understanding of ‘veterans’ culture’ and the specific issues veterans face among ‘front line’ staff dealing with substance and alcohol misuse.

As a result of the research, one possible solution identified as worthy of further exploration is a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model of care. At the centre of the hub would be a military veteran peer support worker, with knowledge of local and national services, and experience in navigating existing pathways of care. This solution perhaps offers one way in which UK military veterans experiencing alcohol misuse problems might engage with the full range of existing services in a considered and individually bespoke way.

Reference:

- Ministry of Defence (2015) Annual Population Survey: UK Armed Forces Veterans residing in Great Britain 2015. Bristol: Ministry of Defence Statistics (Health).

National Conference – Northumbria University and Royal British Legion

Veterans Substance Misuse: Breaking Down Barriers to Integration of Health and Social Care

Newcastle United Football Club (Heroes Suite)

Thursday 16 November

More information on the Fuse website.

Labels:

2017,

alcohol,

commissioning,

families,

focusgroups,

GMcGill,

institutionalisation,

interviews,

military veterans,

National Alcohol Awareness Week,

NorthumbriaUniversity,

peer support,

research,

review

Friday, 27 October 2017

The myth of a dangerous ‘underclass’: a real horror story for Hallowe’en

Guest post by Stephen Crossley, Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Northumbria University

In Victorian times, the middle and upper classes of London spent a great deal of time going ‘slumming’, visiting poorer parts of the East End for various reasons, including their amusement and titillation, and for philanthropic and journalistic purposes.[2] In 1883, George Sims, an English poet, journalist, dramatist and novelist, began his book How the Poor Live by inviting the reader to go a journey with him, not across oceans or land, but ‘into a region which lies at our own doors – into a dark continent that is within easy walking distance of the General Post Office’.[3] Sims hoped that this continent would be:

Indeed, in recent times, the former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Ian Duncan Smith argued that the television programme Benefits Street offered the middle classes a window into the ‘twilight world’ of neighbourhoods where many people received financial support from the state.[5] The ‘twilight world’ of welfare dependency that Duncan Smith refers to elicits feelings of mystery, anxiety, and the unfamiliar, feelings of nervous excitement that the original social explorers must have felt in the late nineteenth century or what middle class travellers of today might experience whilst ‘doing the slum’ on foreign holidays.

Indeed, in recent times, the former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Ian Duncan Smith argued that the television programme Benefits Street offered the middle classes a window into the ‘twilight world’ of neighbourhoods where many people received financial support from the state.[5] The ‘twilight world’ of welfare dependency that Duncan Smith refers to elicits feelings of mystery, anxiety, and the unfamiliar, feelings of nervous excitement that the original social explorers must have felt in the late nineteenth century or what middle class travellers of today might experience whilst ‘doing the slum’ on foreign holidays.

Whilst the words have changed slightly, the myth of a dangerous ‘underclass’ who dwell in ‘dreadful enclosures’ or ‘sink estates’, and who represent a threat to wider society remains. If we want a real horror story for Hallowe’en, we need look no further than how large sections of society view a mythical ‘underclass’ and how they view the places associated with impoverished communities.

Dr Stephen Crossley is a Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Northumbria University. His first book In Their Place: The Imagined Geographies of Poverty is out now with Pluto Press. He tweets at @akindoftrouble

References:

With Hallowe’en nearly upon us, many parents will be telling their children tales of ghouls and ghosts that can be found in haunted houses. Adults will entertain themselves by watching horror movies and other productions where other-worldly creatures and monsters intrude upon peaceful and civilised spaces to threaten the status quo and the existing order of things. Most of us know that ghosts, spirits, and the like are the stuff of legend and lore and tend not to believe the mythology associated with them. But many people in contemporary society do believe in myths about groups of people that are different to the rest of ‘us’, who exhibit different social norms and values to the mainstream population, and who invoke fear and dread in many of us. Many people watch the behaviour of ‘the underclass’,[1] in the name of entertainment, with a mixture of fear, horror, fascination, and contempt. The ‘underclass’, it is believed, can be found in certain locations. There is a long history to such beliefs.

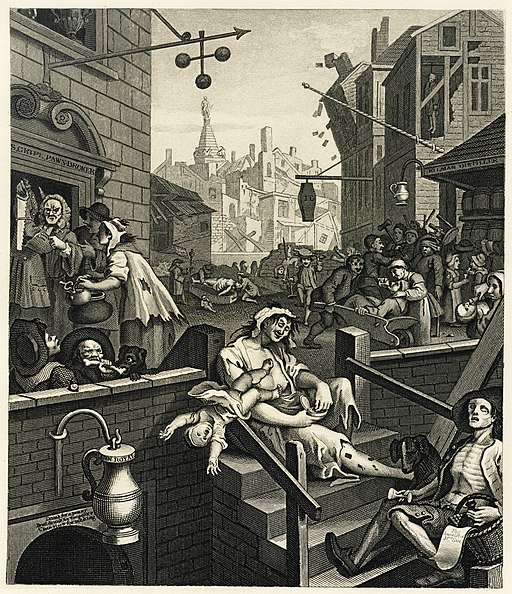

|

| William Hogarth's depiction of London vice, Gin Lane. |

As interesting as any of those newly-explored lands which engage the attention of the Royal Geographic Society – the wild races who inhabit it will, I trust, gain public sympathy as easily as those savage tribes for whose benefit the Missionary Societies never cease to appeal for funds.William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army argued in 1890 that certain areas of London were like parts of Africa that had just been discovered by explorers such as Henry Morton Stanley Africa, and were similarly full of primitives and savages. In 1977, the sociologist E.V. Walter noted that, whilst such beliefs had changed somewhat, traces of them remained:

In all parts of the world, some urban spaces are identified totally with danger, pain and chaos. The idea of dreadful space is probably as old as settled societies, and anyone familiar with the records of human fantasy, literary or clinical, will not dispute a suggestion that the recesses of the mind conceal primeval feelings that respond with ease to the message: ‘Beware that place: untold evils lurk behind the walls’. Cursed ground, forbidden forests, haunted houses are still universally recognised symbols, but after secularisation and urbanisation, the public expression of magical thinking limits the experience of menacing space to physical and emotional dangers.[4]

Indeed, in recent times, the former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Ian Duncan Smith argued that the television programme Benefits Street offered the middle classes a window into the ‘twilight world’ of neighbourhoods where many people received financial support from the state.[5] The ‘twilight world’ of welfare dependency that Duncan Smith refers to elicits feelings of mystery, anxiety, and the unfamiliar, feelings of nervous excitement that the original social explorers must have felt in the late nineteenth century or what middle class travellers of today might experience whilst ‘doing the slum’ on foreign holidays.

Indeed, in recent times, the former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Ian Duncan Smith argued that the television programme Benefits Street offered the middle classes a window into the ‘twilight world’ of neighbourhoods where many people received financial support from the state.[5] The ‘twilight world’ of welfare dependency that Duncan Smith refers to elicits feelings of mystery, anxiety, and the unfamiliar, feelings of nervous excitement that the original social explorers must have felt in the late nineteenth century or what middle class travellers of today might experience whilst ‘doing the slum’ on foreign holidays.Whilst the words have changed slightly, the myth of a dangerous ‘underclass’ who dwell in ‘dreadful enclosures’ or ‘sink estates’, and who represent a threat to wider society remains. If we want a real horror story for Hallowe’en, we need look no further than how large sections of society view a mythical ‘underclass’ and how they view the places associated with impoverished communities.

Dr Stephen Crossley is a Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Northumbria University. His first book In Their Place: The Imagined Geographies of Poverty is out now with Pluto Press. He tweets at @akindoftrouble

References:

- John Welshman, Underclass: A History of the Excluded Since 1880 (2nd edition), London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

- Seth Koven, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London, Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2004.

- George Sims, How the poor live, London: Chatto & Windus, 1883, p1.

- E.V. Walter, Dreadful Enclosures: Detoxifying and Urban Myth, European Journal of Sociology, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1977), p 154.

- BBC News online, Benefits Street reaction shows poor 'ghettoised', says Duncan Smith, 23 January 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-25866259 [Accessed 27 November 2016]

Images:

- William Hogarth [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Generations' (8690911868_23ce2c05a0_z) by ‘Byzantine_K’ via Flickr.com, copyright © 2013: https://www.flickr.com/photos/november5/8690911868

Friday, 20 October 2017

Monopoly money, pitching to the converted, and sending Mr Grumpy away happy: doing home and healthy ageing research differently

Dr Philip Hodgson, Senior Research Assistant, Northumbria University

Endings are rubbish, right? Whether it be a great novel, play, film, TV series – there’s always that feeling that no matter how things are pulled together, it will never be as good as you have pictured in your imagination. And then, you know, it just ends…

It was perhaps with this in mind that we decided to take a different approach in the last of our four workshops on home and healthy ageing. Rather than guest speakers being invited to share their knowledge and prompt discussion, the project team attempted to summarise and pitch their ideas for future research back to the group (think Dragons’ Den). This proved to be challenging, as the previous sessions had been so rich that even synthesising them into brief slides was difficult, never mind placing them in a strategic context for the participants to critique and reflect upon. Yet, three key themes were identified. These were in addition to the concept of a ‘home’ being more than just bricks and mortar but personal/psychological, physical and social/environment space(s) – an idea that we used as a starting block in week one and illustrated below.

|

| More than just bricks and mortar 'Home' illustration used in the seminars |

The key themes were:

- Policies and contexts: not only a tension between housing and health policies, but also the need to consider market and narrative factors influencing housing and health decisions;

- The life course approach: the need to think about housing as an individual pathway, in which preventative measures and services are considered before crisis point;

- Transitions and soft services: the need for support to be available as and when people experience key housing and life changes, such as reduced physical health, retirement, or the loss of support networks and being able to navigate different services on offer.

However, this is where we’d like to leave you with a cliff hanger: rather than going through each of themes in-depth (fans of this series will have to wait for our spin off… er, research papers for that!), we’d instead like to reflect on our process at this stage. These sessions took a slightly different approach as, rather than being a series of open seminars with presentations that people could dip in and out of, we invited several key individuals to attend each session in turn. The reasons for this were many, but primarily we wanted to ensure that a diverse range of backgrounds were represented throughout (housing providers, architects, academics, local authority workers, homelessness workers, etc.) to go on a learning journey with us as a research team. This meant that by the time we reached the final session, there was enough of a shared understanding that we could make the most of the group’s commitment to the project – we would be actually able to start to pin down quite complex concepts, practical issues and, hopefully, future projects.

We tried out different formats to structure the discussions: from world cafés, to games (with Monopoly money!) with researchers pitching ideas to mock panels, which worked to various degrees but always ensured a lively debate.

|

| Do not pass Go. Do not collect £200 Pitching ideas with Monopoly money |

There were, of course, some difficulties. As I’m sure everyone reading this will know, it is a lot to ask of a practitioner to take one morning out of their schedule, let alone for four seminars. As a result, engagement had to remain a constant focus and I spent much time nervously lingering by the registration desk hoping for just a few more name badges to disappear before we started! It was also a challenge in terms of managing the conversations during the sessions: you want all voices to be heard in such a diverse group but we all needed to be pulling in the same direction by the end.

Yet, by the final session, the rewards were immense. Not only were we able to pitch ideas to a group who had already undergone some of the same learning as us, but this gave everybody the confidence to relate the complex theoretical issues to their own practice (allowing us to capture the breadth of what was possible). It allowed us to discuss concrete projects, and leave the session with a sense of trust that networks were in place to actually deliver on them. Perhaps most importantly we found that, what started as a broad idea, was something of relevance across the housing and health sectors. Even the grumpiest of the project group (naming no names) left the day with a spring in their step. For that alone, everyone who attended deserves some massive thanks…

So, who needs endings, when we can all just sign up to the sequel?

To be continued…

Photo 2: By James Petts from London, England (Monopoly) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Labels:

2017,

ageing,

context,

engagement,

environment,

home & health,

Housing,

networks,

NorthumbriaUniversity,

PHodgson,

physical health,

policy,

practice,

psychological,

research,

retirement,

social,

workshop

Friday, 13 October 2017

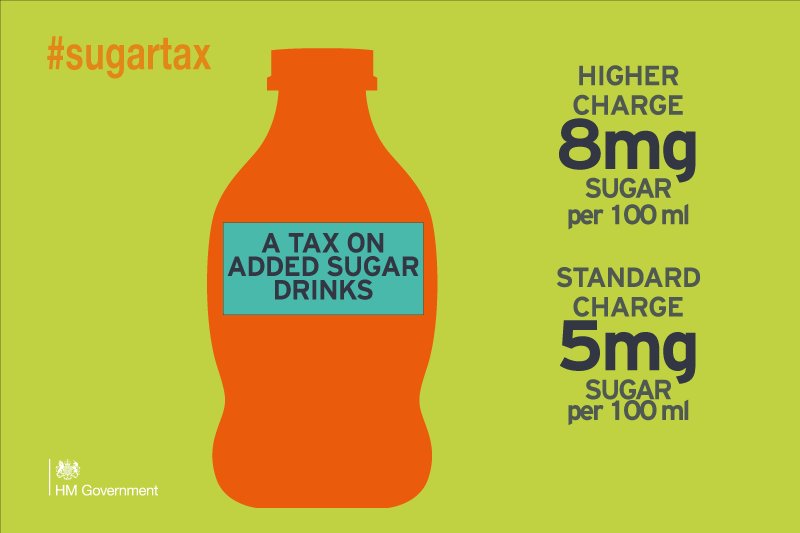

From shock to the system, to system map and beyond: evaluating the UK sugary drinks tax

Mostly you don’t get to watch TV at work. The day that George Osborne announced he would introduce a tax on sugary drinks in the UK, here at CEDAR HQ we all stood huddled around a computer monitor watching and re-watching the words coming out of his mouth.

Oh. My. Goodness. I did not see that coming.

|

| The “soft drinks industry levy”, to give it it’s proper name. |

After we’d got over the shock of the announcement, the conversation turned pretty quickly to research (well, this is a university, after all). We have got to evaluate this!

Colleagues at CEDAR had already written papers about how sugary drink taxes could be evaluated. We had talked with colleagues in other countries about evaluating their taxes – only for those taxes to fall through at the final political hurdle. I have more than one half-written application for research funds to evaluate sugary drink taxes stashed down the back of my computer.

And here it was, all systems go for designing an evaluation for a UK sugary drinks tax! In our back yard!

OK, so we have to work out whether it impacts on diet. But, what about jobs? Will people lose their jobs? Surely we need to know if it changes price and purchasing of sugary drinks. Right, but even if it does people might just shift to other foods – maybe they will just eat more cake instead? We are Public Health researchers, we need to focus on health: does the tax change how many people get diabetes? Or tooth decay? Or the number of obese children? And what about how this even happened? Did you see it coming? Why has this happened? Why now? Why don’t we do interviews with politicians and find out how it happened?

Woah, woah, woah! Ten seconds in and this is getting way more complicated than we (I) had ever thought it might. Before we did anything, we needed to work out what we thought might be going on here. Once we understood what the potential impacts might be, then we could start thinking about how we might evaluate them.

So that’s what we did. We spent 6 months developing a ‘systems map’ of the potential health-related impacts of the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy (aka sugary drinks tax). The tax is explicitly designed to encourage soft drinks’ manufacturers to take sugar out of their drinks. There are two levels – a higher tax for drinks with the most sugar, a lower one for only moderately sugary drinks. So we started there (at ‘reformulation’) and worked out.

Then we sense-checked our map with people working in government, charities, and the soft drinks industry. They made lots of suggestions for things we’d missed, or needed to clarify. We changed our map and asked people to check it again. We changed it again. Only then did we decide what we should, and could, evaluate.

|

| The current version of our systems map (we still think of it as a work in progress). Larger version here. |

Yes, we are going to look at how the price of sugary drinks changes over the next few years. But we are also going to look at the amount of sugar in soft drinks in UK supermarkets, and the range of drinks available. We’re going to use commercial data to look at purchasing of soft drinks, as well as other sugary foods. We’ll use the National Diet & Nutrition Survey to explore whether there are any changes in how many sugary drinks, and other sweet foods, people in the UK eat. We’ll use hospital data to see if the number of children admitted with severe dental decay decreases. We’ll use statistical modelling to predict how changes in how many soft drinks people drink might translate into cases of diabetes and heart disease. We’ll look at the impact of the tax on jobs, and the economy. We’ll explore the ‘political processes’ of why and how this tax happened at this time. And we’ll conduct surveys to find out what people in the UK think of sugar, sugary drinks, and the tax itself – and whether this changes over time.

Obviously it’s going to be a lot of work. We’re going to need some excellent people to join the team to help us actually do this thing. Personally, I’m feeling a little overwhelmed/excited/overwhelmed/excited. It’s going to be brilliant!

Wanna be part of it?

Friday, 6 October 2017

Looking for trouble: deceit and duplicity in the Troubled Families Programme

Introduced by Peter van der Graaf

Guest post by Stephen Crossley, Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Northumbria University

Many families facing health problems, limiting illnesses, or with disabled family members have been labelled as ‘troubled families’ under the government’s Troubled Families Programme. Originally established following the 2011 riots to ‘turn around’ the lives of 120,000 allegedly anti-social and criminal families, the programme is now in its second phase and is working with a far larger group of families, many of whom experience troubles, but don’t necessarily cause trouble. In April of this year, the focus of the programme shifted again in an attempt to improve the number of so-called ‘troubled families’ who moved back into employment, despite the majority of them being in work and many of the remainder not being expected to be looking or available for work.

The programme has been dogged by controversy from day one. Research about families experiencing multiple disadvantages was misrepresented at the launch of the programme to provide ‘evidence’ that there were 120,000 troublesome families in England. The government has since been accused of suppressing the official evaluation of the first phase of the programme after it found ‘no discernible impact’ of the programme and also of ‘over-claiming’ the 99% success rate of the first phase.

|

| David Cameron with Louise Casey, former Director General of Troubled Families |

Many health workers will be involved with the delivery of the Troubled Families Programme in their day-to-day work, although there is also a good chance that they will not be aware of it. Many local authorities do not refer to their local work as ‘troubled families’ because of the stigmatising rhetoric and imagery associated with it. Many families are not aware that they have been labelled as ‘troubled families’ for the same reason, and because it would undoubtedly hinder engagement with the programme. They are not always made aware that the data that is collected on them as part of the programme, is shared with other local agencies and, in an anonymised format, with central government.

My PhD research, conducted in three different local authority areas, found that the programme was based on, and relied upon duplicity from design to implementation. Despite government narratives about the programme attempting to ‘turn around’ the lives of ‘troubled families’, the programme appeared to be more concerned with helping to restructure what support to disadvantaged families looks like, and reducing the cost of such families to the state.

For example, support – both symbolic and financial - for universal services, such as libraries, children’s centres and youth projects, is reducing. Direct financial support to marginalised groups is also being cut, with welfare reforms hitting many of the most disadvantaged groups hardest. These forms of support, and many other more specialist services, are being replaced, rhetorically at least, by an intensive form of ‘family intervention’ which allegedly sees a single key worker capable of working with all members of the family, able to ‘turn around’ their lives no matter what problems, health-related or otherwise, they may be facing or causing.

The simplistic central government narrative of the almost perfect implementation of the Troubled Families Programme was not to be found ‘on the ground’, where there were multiple frustrations and concerns about the depiction of the families and the programme, and numerous departures from the official version of events. Despite the rhetoric of ‘turning around’ the lives of ‘troubled families’, in the face of cuts in support and benefits to families, my PhD thesis concluded that the Troubled Families Programme does little more than intervene to help struggling families to cope with their poverty better, despite the efforts of local practitioners.

Put simply, the programme does not attempt to address the structural issues that cause many of the problems faced by ‘troubled families’, but instead encourages them to ‘learn to be poor’. In my previous Fuse blog, I drew on the concept of ‘lifestyle drift’ advanced by David Hunter and Jenny Popay: where the focus of interventions drifts towards attempting to change individual behaviour, despite the wealth of evidence pointing to other solutions. There is no room in the narrative for wider determinants of people’s circumstances. Because of this, the government’s Troubled Families Programme will do little to turn around the lives and health of the families it claims to help.

A summary of Stephen Crossley’s PhD research can be found here. His first book In Their Place: The Imagined Geographies of Poverty is out now with Pluto Press. He tweets at @akindoftrouble

Photograph ‘Almost 40,000 troubled families helped’ (14087270645_3453006d12_c) by ‘Number 10’ via Flickr.com, copyright © 2014: https://www.flickr.com/photos/number10gov/14087270645

Labels:

2017,

disability,

disadvantaged,

evaluation,

government,

inequalities,

local authorities,

NorthumbriaUniversity,

PhD,

policy,

politics,

SCrossley,

social determinants of health,

troubledfamilies,

welfare benefits

Friday, 29 September 2017

Brands, bottles and breastfeeding: sharing stories of early motherhood

Introduced by Nat Forster

My own story of infant feeding is based in a community where breastfeeding was, and still is, not the norm. I was the first in my immediate family to breastfeed and I struggled with it in various ways. My breastfeeding journey ended much sooner than I had originally planned, when my son was just six weeks old. Two years later, my own sheer determination helped me to feed my second child, a daughter, for nine months.

|

| Justine's first steps into motherhood |

The guilt I felt for breastfeeding my first child for a short time stayed with me for a long time. I did not understand why it had such an impact. Why did I feel the need to breastfeed when others around me did not appear to give breastfeeding a second thought? When the opportunity came for me to undertake PhD research, my choice of topic was never in doubt.

My research, which is supervised by Dr Deborah James from Northumbria University, is focused on the infant feeding stories of nine women who live in an area where breastfeeding rates are low. All of the women’s stories are equally important however, for the purposes of this blog I would like to introduce you to Claire (names have been changed to preserve anonymity), who formula fed her baby Sophia from birth.

Claire, her parents and grandparents have lived in the same local area all of their lives. Claire was a single parent and lived with Sophia’s grandparents when her daughter was first born. Sophia’s grandmother took an active part in her care. She looked after Sophia for two nights a week when she was first born, reducing this to just one night per week as time passed. Following a biographical narrative approach, which allows participants to tell their stories without interruption, I asked Claire for her story with the use of a single question;

"So, please can you tell me the story of your experiences of feeding milk to your baby?"

"Well I started when I was pregnant, erm, I’ve always wanted to bottle feed her er, cause there was pink bottles that I wanted to get her erm and also knew the milk that I wanted to put on her erm, and just bottle feeding become very easy to us."

Claire’s story was dominated with discussion of branding and consumer goods. The pink bottles and the various brands of infant formula Claire gave to Sophia reveal the way media and advertising can influence infant feeding practice. Claire demonstrates that she was careful with her bottle-feeding choices. These choices were not arbitrary; she made clear decisions between brands and bottles. Claire wanted me to know that she had made the right choices for her and her daughter.

It was also quite clear that Claire’s identity, as the mother of a daughter, was an important part of her story. The ‘pink’ bottles represent this in a very visible way, she could perform her identity as a mother of a daughter with the right choice of bottle. Claire’s relationship with her own mother was important to her and she appeared keen to demonstrate that this mother-daughter bond would continue for another generation.

These stories help us to understand why some women breastfeed and others do not. Upon reflection, for me, I feel that breastfeeding was about being the best mother I could be, which explains the guilt I felt when I stopped. For Claire, feeding her baby was also about the same thing, only for Claire, being a good mother was about making the right consumption choices. In my thesis, I expand on how Claire’s choices were based on the social norms, the unwritten rules of how to be a mother, in the culture around her.

Labels:

2017,

advertising,

brands,

breastfeeding,

childcare,

children,

community,

Grandmothers,

guilt,

identity,

JGallagher,

media,

motherhood,

NForster,

NorthumbriaUniversity,

PhD,

pregnancy,

storytelling,

Sure Start,

thesis

Friday, 22 September 2017

The impact of advice services on health: moving from gut feeling to concrete evidence

Introduced by Sonia Dalkin

Guest post by Alison Dunn, CEO of Citizens Advice Gateshead

Citizens Advice Gateshead provides independent, impartial, confidential and free advice to people who work or live in Gateshead about their rights and responsibilities. Gateshead is an area of high deprivation. Overall, Gateshead is the 73rd most deprived local authority in England, out of 326 local authorities. Nearly 23,600 (12%) people in Gateshead live in one of the 10% most deprived areas of England. Nearly 49,800 (25%) live in the 20% most deprived areas (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015).

As a result, our work is predominantly around social welfare issues to include housing, money advice, welfare benefits, relationship and family issues, employment and consumer. In 2016/17 we helped 10,820 people with 71,487 advice issues. We estimate our work has a value to the wider governmental system of £11.5m.

Physical health and mental health are inextricably linked. People with a mental illness have higher rates of physical illness and tend to die 10 – 20 years earlier than the general population, largely from treatable conditions associated with modifiable risk factors such as smoking, obesity, substance abuse, and inadequate medical care (Mykletun et al. (2009). Poor mental health is associated with an increased risk of diseases such as cardiovascular disease (Dimsdale, 2008), cancer (Moreno-Smith et al., 2010) and diabetes (Faulenbach et al., 2012), while good mental health is a known protective factor. Poor physical health also increases the risk of people developing mental health problems.

For us, the link between our advice and health and wellbeing is obvious but persuading commissioners, policy makers and decision makers requires more than a gut feeling. So we feel very privileged indeed for the opportunity to work with Fuse and the research team at Northumbria University to investigate what we have always thought to be true, that our advice reduces stress and anxiety and improves wellbeing for our clients.

The research constituted of a realist evaluation (the protocol of which is detailed here) of three of our more intensive services – one for those with enduring mental health conditions, one for young people, and one for those referred through their GP. The research indicated that stress was decreased and wellbeing increased as a result of accessing the service, using the Perceived Stress Scale and Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale. The research also tells us that our intensive advice services increase the options available to our clients, allowing them to be able to participate in more activities to promote wellbeing and reduce isolation. The service also creates trusting relationships with our clients, which was essential in maintaining relationships in order to help clients with their issues. Finally, the service works as a buffer between the client and state organisations such as the job centre and the Department of Work and Pensions, allowing the two to interact more efficiently.

We plan to maintain our relationship with the research team and we are starting to talk to them about how we can build on this work to learn even more about the link between advice services and the wellbeing of our beneficiaries.

If you would like more information related to Citizens Advice Gateshead, please visit our website: https://www.citizensadvicegateshead.org.uk/

References:

- DEPARTMENT FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT. 2015. English indices of deprivation 2015 [Online]. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/465791/English_Indices_of_Deprivation_2015_-_Statistical_Release.pdf [Accessed].

- DIMSDALE, J. 2008. Psychological Stress and Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 51, 1237-1246.

- FAULENBACH, M., UTHOFF, H., SCHWEGLER, K., SPINAS, G., SCHMID, C. & WIESLI, P. 2012. Effect of psychological stress on glucose control in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 29.

- MORENO-SMITH, M., LUTGENDORF, S. & SOOD, A. 2010. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future Oncology, 6, 1863-1881.

- MYKLETUN, A., BJERKESET, O., OVERLAND, S., PRINCE, M., DEWEY, M. & STEWART, R. 2009. Levels of anxiety and depression as predictors of mortality: the HUNT study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195, 118-125.

Labels:

2017,

ADunn,

citizens advice,

disease,

drugs,

evaluation,

Gateshead,

government,

inequalities,

isolation,

local authorities,

mentalhealth,

obesity,

pensions,

policy,

smoking,

social welfare,

wellbeing,

youngpeople

Friday, 8 September 2017

Postcards from a public heath tourist #2: Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Guest post by Emma Simpson, Research Assistant, Newcastle University

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A few of our academics are lucky enough to have the opportunity to travel around the world to speak at conferences or explore collaborations - all in the line of work and the translation, exchange and expansion of knowledge of course.

The least we could expect is a postcard, to hear all about the fun that they're having while we’re stuck in the office watching droplets of rain compete in a race to the windowsill…

Here’s the second from Emma Simpson.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear Fuse Open Science Blog,

It’s not just academics who get amazing opportunities, PhD students do too!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A few of our academics are lucky enough to have the opportunity to travel around the world to speak at conferences or explore collaborations - all in the line of work and the translation, exchange and expansion of knowledge of course.

The least we could expect is a postcard, to hear all about the fun that they're having while we’re stuck in the office watching droplets of rain compete in a race to the windowsill…

Here’s the second from Emma Simpson.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear Fuse Open Science Blog,

It’s not just academics who get amazing opportunities, PhD students do too!