In an age when public health and health improvement efforts in much of the world are justifiably focused on chronic disease, lifestyle factors and the ever increasing health and social care needs of an ageing population, we would do well to remember that humankinds’ most determined and persistent adversaries are always “waiting in the wings” ready to step on the stage for a lead role once again.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses, some causing (mostly mild) illnesses in people and others that circulate among animals, including camels, cats and bats. The recently emerged 2019-nCoV is not the same as the coronaviruses that caused Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) though genetic analyses so far suggests that the new variant is more closely related to SARS[3].

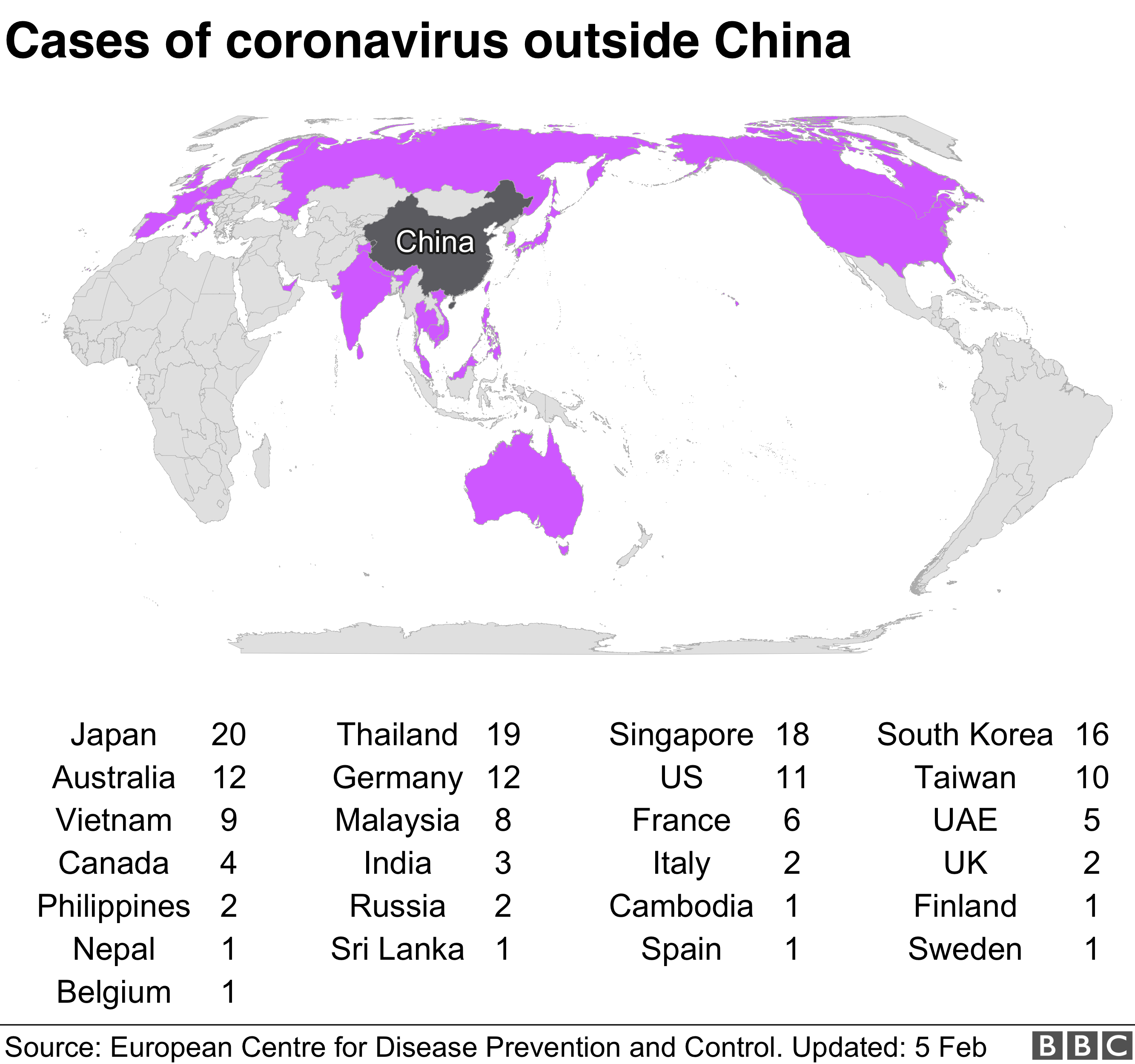

Ninety Nine percent (99%) of the 24,000+ cases and nearly all of the 490 confirmed deaths (with 2 exceptions, one in Hong Kong and one in the Philippines) so far have been in China. Despite this, the WHO emergency declaration crucially allows for additional resources and support for lower and middle-income countries to strengthen their disease surveillance and prepare them for potential cases or outbreaks. At the present time, to the considerable credit of the Chinese response – partly arising of course from international condemnation of a less than transparent response to the SARS outbreak in 2003 – there are Herculean efforts and resources being devoted to containing the threat from the new pathogen. This includes the drastic attempted quarantine of a whole region and the speed of construction of new facilities such as 1000 bed dedicated hospitals.

While 2019-nCoV seems to be less lethal than SARS, there is no doubt that it is clearly more transmissible with The World Health Organization stating that the preliminary R0 (reproduction number) estimate is 1.4 to 2.5, meaning that every person infected can potentially infect between 1.4 and 2.5 people (R0 for SARS being 0.19–1.08, with a median of 0.49)[4]. With the spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild respiratory illness to life threatening viral pneumonia, the health impact of the ongoing outbreak is very difficult to predict and unanswered questions abound. How many people may have shrugged off mild / virtually asymptomatic infections for instance is not possible to know until follow-up sero-conversion studies[5] can be used to estimate the burden of ‘silent infections’.

Aside from higher transmissibility, the more worrying aspect of 2019-nCov however is the reports of an incubation period of up to 14 days during which an infected individual might both be asymptomatic (displaying no evident symptoms that could be screened for) and also crucially, at the same time during this period, infectious and capable of transmitting the virus to new hosts. The potential 14 day incubation period without symptoms effectively means that the cases which are being confirmed at the present time merely reflect the ‘true burden of infection’ from two weeks ago. As a result we will only have any real sense of the effectiveness of Chinese efforts to contain the virus a fortnight after the stringent travel restrictions imposed around Wuhan province and other parts of China.

As many seasoned experts in these matters have cautioned, schooled as they have been by experience of previous episodes, predicting the behaviour of a newly emergent pathogen is a hazardous business and a great deal of uncertainty surrounds its likely route to potential pandemic status. A virus adapting to a new species host (in this case humans!) is an unstable entity and its defining characteristics today in terms of those who are most vulnerable and their risk of serious or life threatening illness may be very different in the weeks and months ahead.

Eventually of course, a virus keen on longevity in a new host needs to curb its pathogenicity[6] and ideally result in only mild symptoms that will reduce the attention it attracts from a host immune response. Many of the hundreds of viruses, including coronavirus subtypes that cause the common cold, once jumped the species barrier and evolved into relatively benign pathogens. Even the deadly “Spanish flu” epidemic of 1918[7], which killed around 60 million people Worldwide in 1918-1920 and comprised of the influenza subunits H1N1, circulates today in the form of seasonal flu in a genetic variant with greatly reduced lethality.

How serious the current outbreak will be in terms of impact and mortality remains to be seen. SARS of course was eventually successfully contained by stringent infection control, contact tracing and quarantine procedures. While 2019-nCov is not currently as life-threatening an illness as SARS, its greater transmissibility, longer incubation period and potential for symptomless transmission (SARS was only transmissible when symptomatic), do not bode well for ease of containment so it is hardly surprising that the WHO have seen fit to play their strongest card and declare it an emergency.

We can only hope that the response may be timely enough.

John Mooney worked previously for NHS Health Protection where he specialised in the epidemiology of respiratory infectious diseases.

References:

John Mooney worked previously for NHS Health Protection where he specialised in the epidemiology of respiratory infectious diseases.

References:

- Coronavirus declared global health emergency by WHO: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-51318246

- Coronavirus: UK patient is University of York student: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-51337400

- 2019 Novel Coronavirus Basics: CDC FAQs: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html

- Emerg Infect Dis. 2004 Jul; 10(7): 1258–1263 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3323341/

- Seroconversion: The development of detectable antibodies in the blood that are directed against an infectious agent. Antibodies do not usually develop until some time after the initial exposure to the agent.

- Pathogenicity is defined as the absolute ability of an infectious agent to cause disease/damage in a host - an infectious agent is either pathogenic or not. From: Fenner and White's Medical Virology (Fifth Edition), 2017

- 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus): https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html

Image 2: Capture from the BBC News website, 5 February 2020. Coronavirus: Ten passengers on cruise ship test positive for virus. Source: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Updated 5 Feb. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-51381594.

Hi There,

ReplyDeleteYour Blog is very interesting and knowledgeable. Keep doing good work.

Many thanks Mathew - sorry for the delay in acknowledging your feedback - it won't have escaped your notice that the above predicted divergent new strains: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55308211

Delete